Connect Four and Minimax

Computers are incredibly fast calculators. That makes them good at maths, but it does not make them smart. People that program computers have to invent clever ways to exploit that arithmetical ability to achieve intelligent behavior.

Using the force.

Often the simplest way to allow a computer to make the ‘right’ decision is to calculate all possible outcomes and select a path that leads to the best end result. When planning a route from A to B, we consider every possible sequence of turns for every intersection between A and B. This so-called brute-force approach does not require a lot of thinking, it requires a lot of calculating; and computers are pretty good at the latter, less so at the former.

Sometimes it is possible to trim certain paths of exploration because we are certain they will lead to sub-optimal results. For example, when a sequence of turns leads us back to an intersection we have visited before along this route. But even then, this method quickly results in long computation times as the number of possible outcomes grows exponentially with the number of possible decisions the computer has to consider.

This is one of the reasons why we need a super-computer to beat a chess grandmaster. There are a lot of possible moves to consider in a game of chess.

Another problem when programming computers to play a two-player zero-sum game like chess, is that half of the decisions in the game are made by the opponent. The computer can decide which moves to make, but it has no control over what the opposing player does in response.

Even worse, assuming they both want to win, the two players have completely diametric goals. When plotting a potential path through solution space, we have to consider that our opponent probably wants to move towards a different solution altogether. The other player is actively trying to stop us from getting to where we’re going.

One easy way to deal with the uncertainty of the opponent’s decisions when looking ahead is to assume the other player will always make the move that leads to the worst possible result for the computer. The opponent is not trying to win, he is trying to stop the computer from winning. When plotting a path (succession of possible moves) we alternate between making the best (maximum) move when it’s our turn and the worst (minimum) when the opponent is up to make a move.

This approach is called minimax. It is not particularly clever, but it does the trick and is relatively easy to implement.

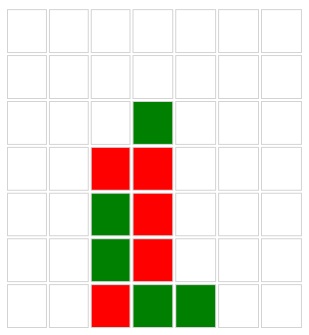

Connect Four.

Last year, a Microsoft SharePoint consultant I’d met at a customer site asked me to explain how to implement a computer opponent for a Connect Four game he was creating for Microsoft Windows Phone Mobile XP 7 Vista Home Edition (or whatever they call it nowadays). Instead of explaining how, I decided to build a simple example myself in JavaScript using minimax. I don’t think he ever finished his version of the game.

You can play my version here. Somewhat ironically, it is excruciatingly slow when using Microsoft Internet Explorer; so please consider using any other browser.

Update (June 29th 2012): The code for this example is available on Github.

Update (July 5th 2012): This is now available as a web service. Read this post.