Research and experimentation are the “peanut butter and jelly” of customer insights — here’s why

Written by Molly Stevens and Lukas Vermeer.

User research and experimentation are both powerful tools that allow us to narrow down and select product options. Each tool has a range of core capabilities that ensure our customers have great experiences and the business reaches their goals.

At Booking.com, our teams collaborate together within an insights organization, focusing on how to measure and understand the customer experience across all aspects of our business. When we (Molly and Lukas) started working together a year ago, people expected that we would not get along. This expectation stemmed from the mistaken idea that somehow our respective fields are in conflict. However, we both know that our disciplines can work well together, although it can be challenging to help our stakeholders and partners in the business understand how our areas are incredibly complimentary.

In this post we will examine in some detail why we consider research and experimentation to be the “peanut butter and jelly” of the customer insights world — two unique things that are even better together. We will give general explanations and specific Booking.com examples. We will also walk you through a recent case study where we’ll examine how focusing on each of our core strengths allows for highly effective evidence-based decision making. We hope this will give you the language for stakeholder discussions to talk about experimentation and research, and how they belong together.

Quant times qual

We have noticed some prevailing myths around experimentation and user research. We believe that these cause confusion and block the ability to collaborate and move forward on key topics. These myths center around a “numbers vs. people” (i.e. experimentation vs. user research) type mentality, which is an unhelpful and unnecessary division.

These myths include:

- Bigger numbers are always more believable, so experimentation is “better”

- User research always takes a long time AND experiments are always faster.

- There is no subjectivity in experimentation, so it’s the only way to be “data driven”.

- User research is expensive and experimentation is free.

- These fields, and the people in them, don’t work well together.

- Choosing just one to focus on is a good business, as well as personal, strategy.

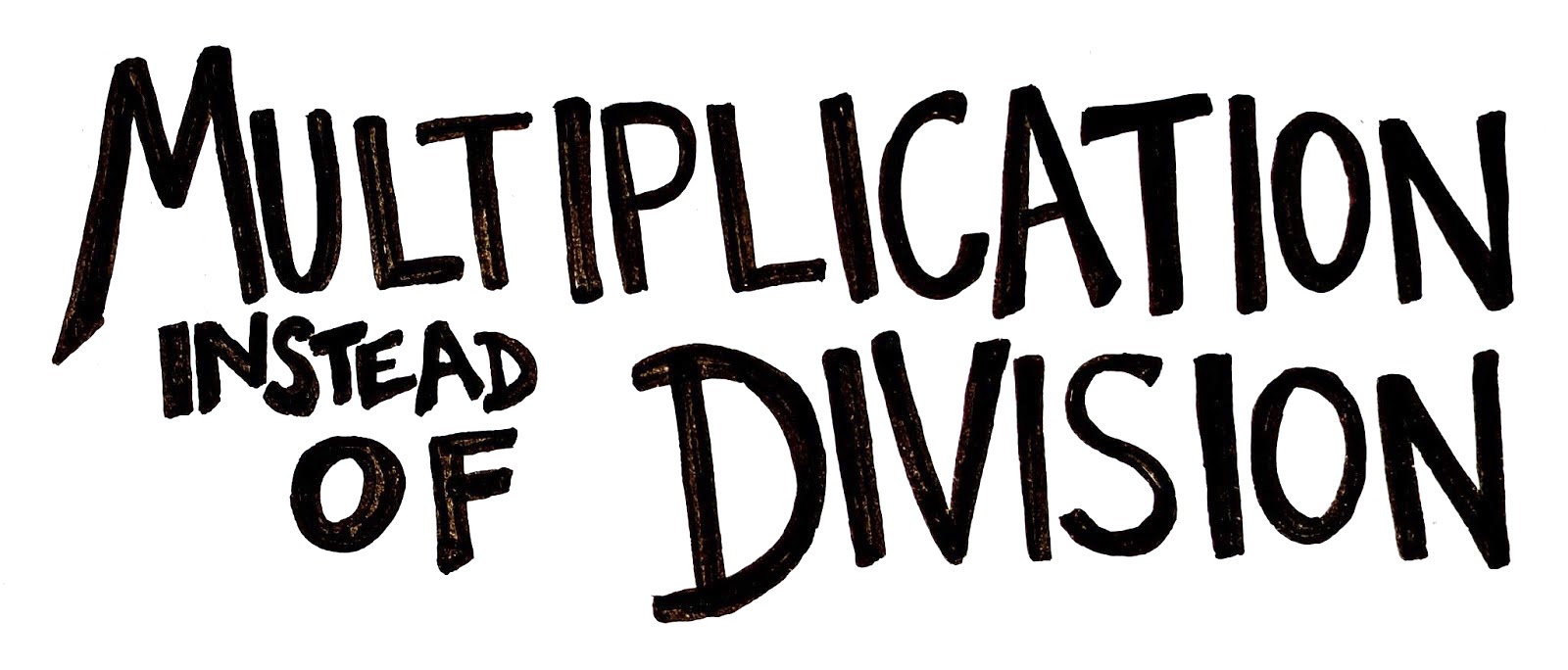

Boiling down the inherent complexity to these black and white views highly limits our ability to recognise how our fields can (and should) work together. When we base our work practices and processes on collaboration, experimentation and research multiply the positive effects of their respective areas. This multiplicative effect on the kinds of positive experiences that can delight our customers and build business. This is especially important to support a company culture that rewards not just success, but learning and evolution.

Instead of thinking in terms of research VERSUS experimentation, we should be thinking how we can use research TIMES experimentation.

Without more knowledge about our areas it could be confusing to understand how this makes sense. In the following section we will define our areas more precisely, illuminating the elements that make us perfect partners.

Research at Booking.com

At Booking.com, research is a multi-method approach to answering questions in two main areas of inquiry around the what and why behind human behaviors. We turn our observations into insight and knowledge which can help us work with our cross-functional partners.

- What do we see currently in the world and on our products?

- What are the hypotheses about future behavior, where we can make changes and improvements?

Gathering the insights to answer these questions, gives us an opportunity to apply the knowledge to three major product development areas that help us understand major customer problems or opportunities.

- Roadmaps. What kinds of products or services should Booking.com be building? What are the key characteristics of these that would meet customer needs?

- Products/Features. When a product/feature is created, or added, how will people react? What are their needs and expectations? Who is the target audience and does this work for them?

- Experiments. Are we taking into account the right potential solutions? Is the experiment targeting the top use cases in the right context?

Understanding the customer, the scope of the problem — and the space in which we are working, helps us to partner with cross functional partners and identify the best solutions. Defining the hypothesis, and understanding what kinds of data will help them to prove or disprove that hypothesis are essential for strong decision making.

Experimentation at Booking.com

At Booking.com, experiments are an important part of our product development cycle. Experiments allow us to measure, in a controlled manner, what impact our changes have on customer behaviour. Every product change we make has a clearly-defined purpose. Measuring the impact of our changes through experimentation allows us to validate that we have achieved the desired outcome. Experiments also allow us to abort changes quickly when they do not have the intended effect.

The term experiment itself seems to be often misunderstood, yet it is actually very clearly defined. Two key concepts are important to understand when talking about experimentation:

- An experiment is a procedure carried out to support, refute, or validate a hypothesis.

- Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs when a particular factor is changed.

This definition is probably a bit more broad than most people tend to call “experimentation”. For example, this concept of experimentation is not limited to only certain kinds of changes. It is also not limited to randomised experiments (often called A/B tests). Put differently, any changes made to a product, with or without the intent to have an impact, could be considered an experiment.

The more prior evidence and understanding is available, the more clearly the hypothesis and change — also called treatment — can usually be formulated. More often than not, much of this prior evidence and understanding will come from prior research. Without clearly defining the hypothesis in advance, there really can be no good experimentation. Data quality and statistical rigor are obviously important factors when running experiments, but it is important to acknowledge that these cannot fix a weak hypothesis or an inferior treatment.

We use experimentation to help us validate hypotheses with the goal of addressing well defined user problems. It’s all about learning as fast as possible in the most rigorous way possible. — (Finn Hansen, Senior Product Manager, Booking.com)

At the product strategy level, there are always (too) many ideas to work on. Here, experiments help us learn which changes have impact. The quicker we manage to validate new ideas, the less time is wasted on things that don’t work, and the more time is left to work on things that make a difference to our customers. Experiments help us decide what we should ask, test and build next.

Evidence-based decision making

It is often said that Booking.com is a “data driven” company. However, data itself is not driving the decisions we make. Instead, we use data as evidence to support our decisions. Humans are still the driving force behind making choices about that data — and how to bring it to each of the decisions they make. Both research and experimentation provide evidence for this decision-making process.

In this context, research can be used to gather data for a broad range of topics, which may or may not have a clearly-defined hypothesis yet. We can use the data from research as evidence in a decision-making process — for very broad and very precise topics. Experimentation, on the other hand, is always centered around clearly-defined hypotheses. Every experiment is designed specifically to collect evidence for one of these hypotheses.

To illustrate how these two fields interact, we will discuss a recent case study.

Traveller needs in coronavirus times

Initially, about a year ago, when COVID-19 closed down the world and travel became both less possible, and in some ways less comfortable, we paused our research for a bit.

Finally as summer came, and things began to open up again, we set out to understand changes in traveller sentiment that had happened during the lockdowns. We knew that we could make a lot of changes to our product offerings, but which ones would be the most meaningful and useful to our population?

Conducting remote interviews and online surveys, we dug into the following topic.

Identify how Booking.com can help customers with the “new” needs:

- What are customers concerned about? What are they looking forward to?

- What do customers expect from Booking.com specifically

- What are the must > nice-to-have product features?

We had multiple findings from this work, however, one significant finding was the following:

Travelers are more likely to stay at apartments/homes when compared to the previous year; hotels might have higher cleaning standards, but homes offer isolation and more control of the environment.

We combined this with knowledge of our customer segments and previous experiments, and then worked with our product teams to develop potential experiments.

From insight to experiments

Whenever we have a key insight like that, there are always many ways in which we can try to address the customer’s needs. In this case, we wanted to help customers find a particular kind of property that we think they will enjoy. The question is how we should change the product to help them do just that.

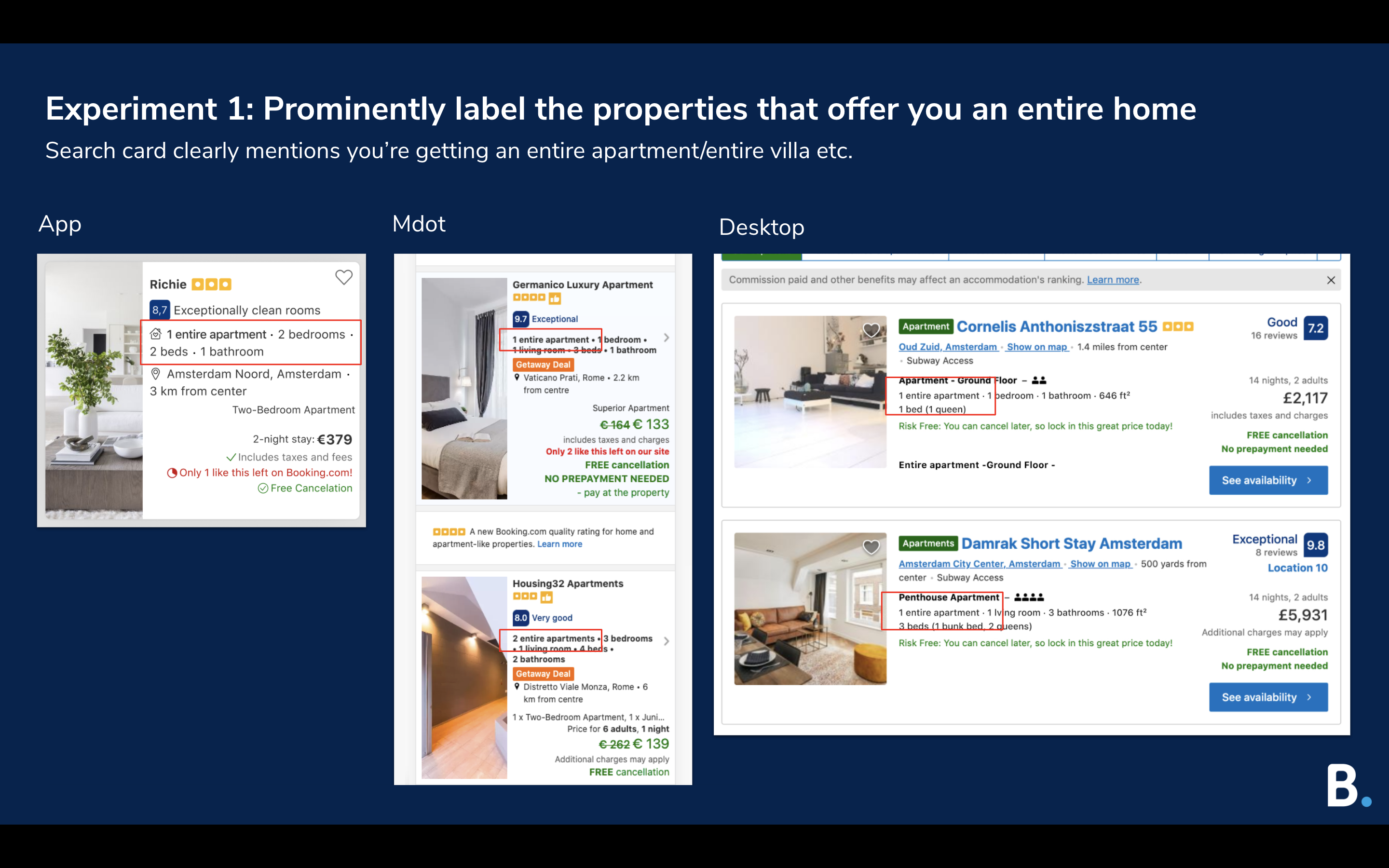

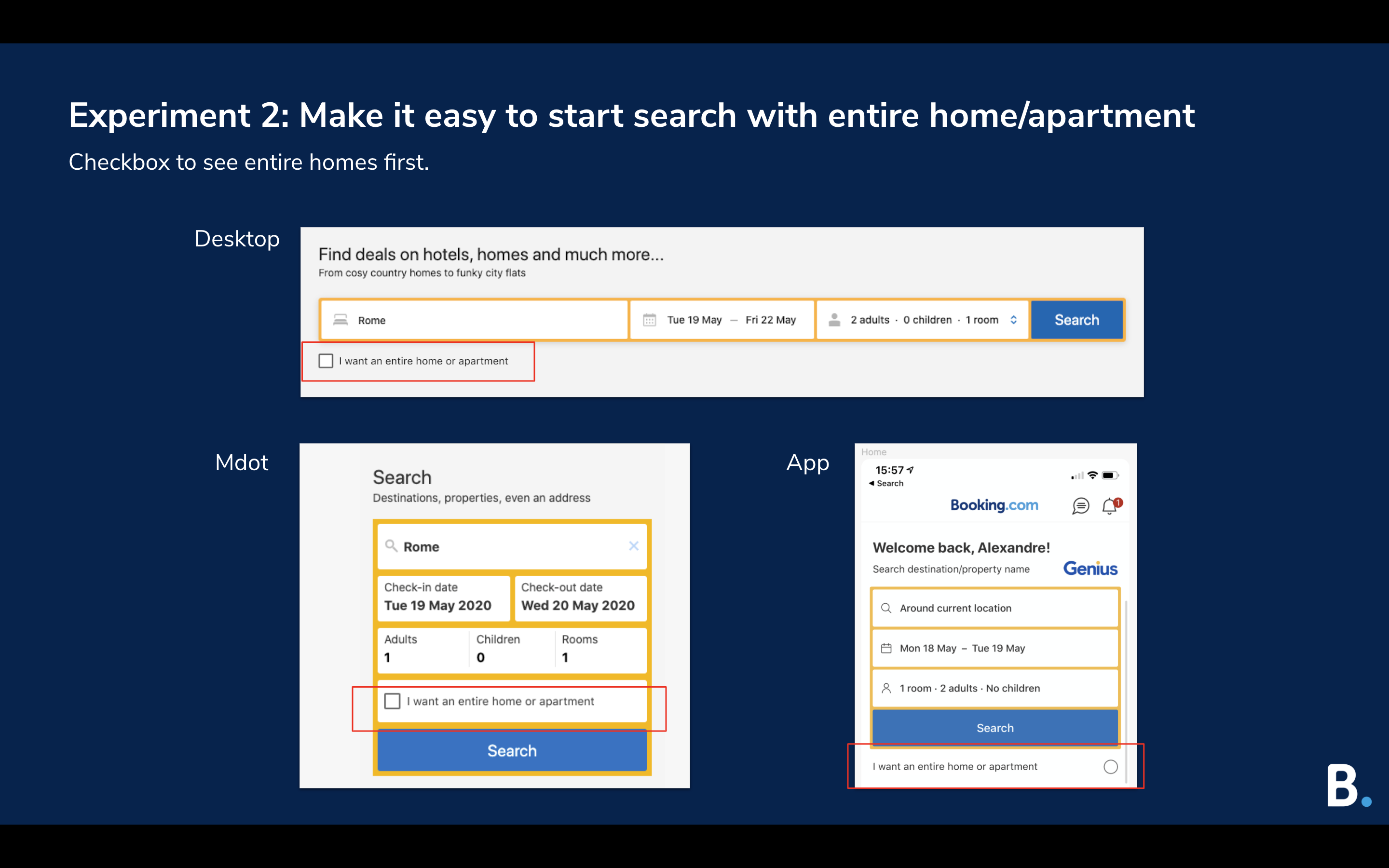

We could for example visually highlight these properties on our search page. Or we could allow customers to explicitly filter for them. Both of these ideas could potentially help people find what they are looking for. At Booking.com, we use experimentation to identify which of these implementations actually do have the expected effect.

In the case of this example, our product teams explored both of the implementation ideas — highlighting and filtering — in a series of experiments. Both lines of experimentation were based on the same core research. Both were trying to address the same customer needs. Where the two differed was in our approach to implementing the solutions. This shows that the relationship between an insight and an experiment is often many-to-many instead of one-to-one.

Both approaches required different product implementation trade-offs to be made. For example, visually highlighting these properties could be added to the existing interface without the need to remove something else. Conversely, the way filtering was implemented meant that another filter was made less prominent in order to make room for the new one.

These differences in implementation turned out to be important. Even though both lines of experimentation were based on the same research and customer needs, the outcomes were very different. Visually highlighting properties proved to help people find what they wanted, while filtering did not have a positive effect. In fact, the filtering approach seemed to have negative side effects for certain customer groups that were not part of the original research. Ultimately, our product teams decided to ship the visual highlights and drop the filtering idea. Experimentation helped them gather the evidence required to decide which change helped our customers reach their goals best.

Our customers got added value from the successful experiment — and they showed this in their behavior. Research can use this knowledge about large scale behavior to investigate and understand what is motivating and exciting for our customers. As we move into this summer, we can try to understand how this is performing — from a qualitative and customer journey POV, which will lead to more hypotheses and experiments.

Conclusion

Experimentation and research are important tools in your toolbox for gathering data — and identifying different hypotheses for customer focused decisions. Our areas are not at odds — each of these disciplines is useful for different things and under different circumstances. We’re a multiplying effect — increasing the efficiency of each other in getting to the BEST solutions thoughtfully and quickly. Partnering together is even more important with the amount of data that our company gathers to understand the customer experience. Turning this data into supporting or disproving evidence supports efforts to de-risk our decisions at each step.

We hope this article has helped you understand as well as express how experimentation and research can partner up to provide deeper and more meaningful insights and better customer experiences. We look forward to hearing your stories about how experimentation and research evolve in your businesses and contexts

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the teams at ADAPT and UXRConf Anywhere 2021 who helped us craft the talks on which this article was based. Thanks to Kristofer Barber for helpfully suggesting improvements and additions to an earlier version of this article. Lastly, we would also like to thank everyone who was involved in the research and experiments outlined in this article.