Estimating Pi

[I’ve tweeted about this before, but I feel the need to explain.]

I want to share with you my favorite algorithm. It may not be pretty, efficient or even practical, but I love it for it’s misleading simplicity and hidden complexity. It is a Probabilistic (Randomized) Algorithm that combines statistics and Euclidean geometry by using the Pythagorean theorem and the Law of Large Numbers to estimate Pi. I first learned about this algorithm when I was at Utrecht University studying Computing Science.

Don’t worry, this is not some complicated computer-gizmo-thing that only super-nerds can translate. I’ll take you through it nice and slow. You will need to recall some basic arithmetic you learned in high-school.

To estimate Pi, we rely on the following truths.

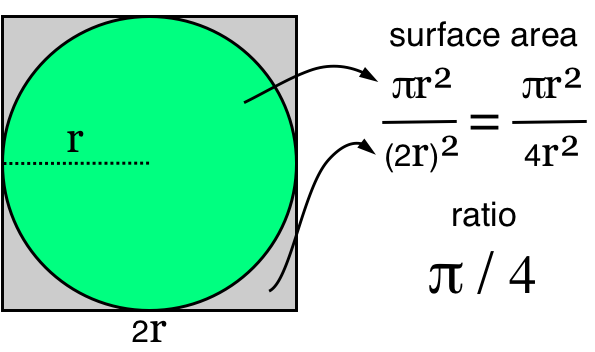

- The surface area of a circle is equal to πr² (Pi times the radius of the circle squared, definition of Pi).

- We can make a square in which the circle fits with sides that are of length 2r (easy, just try it).

- The surface of that square (that just encompasses the circle) is (2r)² (the width of the square squared).

- The ratio between the surface of the circle and the surface of the square is πr² / (2r)²; which equals π / 4.

- This ratio reflects the percentage of the square that is occupied by the circle (something close to 78,5%).

- The odds that a random point in the square is also in the circle is equal to the ratio of the two surface areas (statistics).

- Any point in the square is also in the circle when it is less than r distant from the center of the circle.

- The distance between two points squared is a² + b² (Pythagorean theorem).

- If you select enough random points in the square, the ratio between those points that are also in the circle and those that are not in the circle will approximate the ratio between the two surface areas (law of large numbers).

Based on all this, all we have to do is the following.

- Pick a a bunch of random points in the square (say N number of points where N is a pretty big number).

- Determine how many of those points are in the circle using the Pythagorean theorem (say C of them are in the circle).

- Calculate the ratio between C and N and multiply by 4.

- Presto! You have now estimated Pi. Written down in Perl and compressed to fit into a single tweet this 1 can be expressed as:

perl -e 'for(;$i<999999;++$i){rand()**2+rand()**2>1?0:++$c}print 4*$c/$i." is (probably) pretty damn close to Pi!\n"'

Which probably looks daunting, but does nothing more than what I’ve just described.

for (;$i<999999:++$i)just means “do the following 999999 times”.rand()is a random number between 0 and 1.N**2isNsquared.something ? this : thattranslates to “if something is true, do this, else, do that”.0does nothing.++$cadds one to the variableC.printdoes exactly what you expect.\nprints a new line (solid return). When executed, the Perl script outputs something like the following.

3.14152714152714 is (probably) pretty damn close to Pi!

Which is obviously wrong, but still pretty close to the actual number. Also note, that since we select random points the estimated number will be different every time we execute the code. To increase the accuracy of the number, simply use more random points. As the professor who explained this to an astonished class commented:

For maximum accuracy, you should simply select enough points so that the odds of a technical computational error are higher then the odds of an estimation error.

Isn’t computing science cool!?

-

As my friend Daan pointed out before my original tweet was not quite optimal; hence the different code in this post. ↩