Leaky Abstractions In Online Experimentation Platforms

Categorising Common Challenges

Written by Timo Kluck and Lukas Vermeer.

Online experimentation platforms abstract away many of the details of experimental design, and their users do not have to worry about sampling, randomisation, subject tracking, data collection, metric definition and interpretation of results. The rapid adoption of these platforms in the industry might in part be attributed to the ease-of-use these abstractions provide. However, there are common pitfalls to avoid when running controlled experiments on the web, and one needs experts familiar with the entire software stack to be involved in the process.

In this post, we argue that these pitfalls are not the result of shortcomings specific to existing platforms which might be solved by better platform design. Rather, they are a direct consequence of what is commonly referred to as “the law of leaky abstractions”. That is, it is an inherent feature of any software platform that details of its implementation leak to the surface, and that in certain situations, the platform’s consumers necessarily need to understand details of underlying systems in order to make proficient use of it.

The law of leaky abstractions

Software platforms invariably expose an abstract API to hide certain complexity from their users. However, they can never completely succeed in concealing the intricacies of the underlying subsystems. Computer abstractions are always imperfect. This phenomenon was first described by Kiczales, and the terminology “law of leaky abstractions” was introduced by Spolsky.

Abstractions in online experimentation platforms

Abstraction in software systems is not limited to hiding complexities of underlying software or hardware systems. In many cases, it applies to theoretical concepts or even objects in physical space. Experimentation platforms in particular commonly abstract away the following aspects of experimental design:

- Statistical unit and tracking. The platform determines what is the statistical unit of observation (e.g. login account, cookie or uninterrupted sessions). Then for a given event (e.g. http request) it finds the corresponding unit and tracks accordingly.

- Sampling. The platform imposes treatment to a (usually randomized) subset of traffic. It takes responsibility for ensuring that this selection of current traffic is representative of traffic as a whole. When reporting the resulting metrics, and showing them with confidence intervals and predictions of overall impact, it is implicitly taking responsibility for the assumption that both the treatment and control selections of current traffic are representative of future traffic. It also assumes that on the side of the IT infrastructure, showing treatment to a percentage of traffic has the same (e.g. performance) characteristics as showing treatment to full traffic.

- Definition and implementation of metrics. The platform defines how metrics are gathered and thereby also their exact definition.

- Business meaning of metrics. The platform will likely interpret an improvement in click-through rate, revenue, or conversion as being “good”. It may highlight this result in a positive way, or even end the experiment and select the treatment as the new default.

We observe that all four of these abstractions can leak, in which case the experimenter needs to be well-informed of their intricacies in order to base a sensible decision on the collected data. This has been alluded to by Tang et al.

There are times … where something in the actual implementation goes awry, or something unexpected happens. In those cases, the discussion is as much a debugging session as anything else. Having experts familiar with the entire stack of binaries, logging, experiment infrastructure, metrics, and analytical tools is key.

The conceptual framework put forward in this post can help explain why the need for “experts familiar with the entire stack” cannot be avoided, as well as enable us to categorize common pitfalls in terms of which specific abstraction is leaking.

Examples of leaky abstraction

Let us consider a few known experimentation pitfalls through the lens of leaky abstraction. We will present one example for each of the four categories described above.

Statistical unit and tracking

Most experimentation platforms inform users of how many “visitors” are part of their experiment. However, as Coey and Bailey point out, the number of real human visitors is often unknown.

Identifying the same internet user across devices or over time is often infeasible. This presents a problem for online experiments, as it precludes person-level randomization. Randomization must instead be done using imperfect proxies for people, like cookies, email addresses, or device identifiers.

These imperfect proxies may cause leakage when a treatment affects how well the platform can identify and track visitors.

For example, when users are presented with a new cookie consent banner, more users may decide to delete their cookies. When they do, the experimentation platform is unable to further track their behaviour, causing missing data issues. Different cookie deletion rates between treatment and control result in different degrees of missingness, potentially compromising experiment results.

A key point in this example is that it is the treatment itself that interferes with the platform’s workings. This means that implementing the feature and measuring its impact in an experiment are not concerns that can be separated. The experimenter needs to understand how the platform identifies and tracks visitors.

Sampling

To help explain our second category of leakage, suppose a treatment involves caching certain data for each user. For example, we might introduce a feature that stores the lowest price a user has seen so far in a given destination. For concreteness, let’s say we store that data in a MySQL table. It is very well possible that with 50% of traffic all rows remain cached in memory, whereas with 100% of traffic some queries need to read from disk. This means that the performance observed in the A/B test cannot predict the performance when the feature goes full-on.

In other words: the sampling abstraction is leaking. The platform silently assumes that the exposed sample of traffic is representative of traffic as a whole.

In this case, there is nothing the experimentation platform could do to flag this issue. The experimenter has to rely on their own experience and analysis to foresee this possible problem.

Definition and implementation of metrics

Kohavi et al. describe a situation where a certain experiment showed an unexpected but statistically convincing uplift in click-through rate.

The “success” of getting users to click more was not real, but rather an instrumentation difference. Chrome, Firefox, and Safari are aggressive about terminating requests on navigation away from the current page and a non-negligible percentage of click-beacons never make it to the server. […] Adding even a small delay [in the treatment] gives the beacon more time, and hence more click request beacons reach the server.

In this situation, the metric of “click-through rate” (CTR) is implemented as “successful request beacons reaching the server”. The platform hides the fact that request beacons are part of the implementation and definition of the CTR metric at all. However, just as in the first example, the treatment itself interferes with the platform’s workings, and this metric implementation detail leaks to the surface.

Business meaning of metrics

Many experimentation platforms visually suggest a default interpretation for metrics. An increase in conversion rate is typically considered to be ‘good’ and therefore represented in green. Similarly, a decrease in click-through rate is often considered to be ‘bad’ and represented in red. (At Booking.com, our platform stores metadata to indicate whether an increase is either good, bad, or ugly. Here, ‘ugly’ means ‘not inherently good or bad; do not represent in green/red’. The platform uses a shade of purple to represent this category instead.)

However, this is not always the case. For example, Booking.com has a feature called ‘emergency message’ allowing us to display a warning message if a certain emergency (e.g. a natural disaster) affects the destination where the user is searching for accommodation. We may briefly run this as an experiment to validate that the banner itself has no technical issues. In this case a decrease in conversion, though represented in red, is not bad for our business: in fact it is the expected result of warning users about an emergency. Lower conversion rate in this case is indicative of helping our users avoid a bad experience, which makes good business sense. The abstraction that “down is bad” is leaky.

Mitigating abstraction leakage

The law of leaky abstractions states that leakage is unavoidable. Nonetheless, we propose three general methods for reducing the risks:

- Increased user awareness. Users of experimentation platforms must be made conscious of the abstractions the platform is hiding from them. Personal experience tells us that users are often not aware of the design decisions that were made by platform developers. By making these chosen defaults explicit, users are in a better position to design experiments that work with the platform rather than against it.

- Expert experiment review. Expert review and assistance setting up experiments should be made available when needed. A formal process or some additional user education may be required to help users identify potentially problematic scenarios.

- Automated warnings for known pitfalls. Automated warnings for known pitfalls should be implemented as part of the platform user interface. This can flag potential issues for more in-depth review; possibly aided by experts. Alerting users to potential issues and guiding them in their analysis of the underlying complexity has the added benefit of serving as additional “training on the job”, which might help experimenters better identify future issues which the system does not detect.

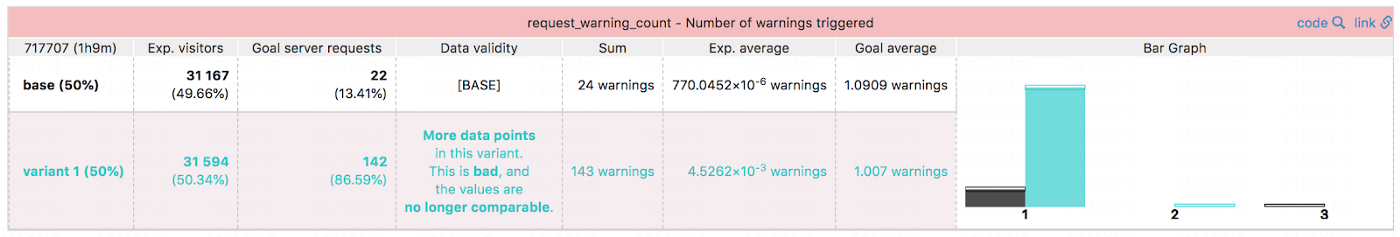

As a practical example, the screenshot below shows how our in-house experimentation platform at Booking.com applies automated warnings as a mitigation strategy in cases similar to the click beacon example described earlier. The infrastructure automatically monitors whether the number of metric related server requests is balanced for any metrics used in any experiment. When an instrumentation difference is detected, users viewing the experiment results are warned that there are “more data points in this variant” (because there were more server requests with any warnings at all) and that this “is bad, and the values (i.e. the number of warnings per request) are no longer comparable.” This approach helps users of all skill levels independently identify, as well as interpret, potential abstraction issues when they occur.

Booking.com’s Experiment Tool warns users about known pitfalls automatically.

Conclusion

In this post we have identified four aspects of experimental design commonly abstracted away by experimentation platforms. We have given examples of leaky abstractions from these four categories and suggested some methods for mitigating abstraction leakage.

We hope that the conceptual framework provided in this post aids implementers and users of online experimentation platforms to better understand and tackle the challenges they face. Leaky abstraction can function as a helpful lens through which to consider several previously known pitfalls.

Acknowledgements

This post was loosely based on a paper presented at the 2015 Conference on Digital Experimentation CODE@MIT. The ideas put forward were greatly influenced by our work on the in-house experimentation platform at Booking.com, as well as conversations with colleagues and other online experimentation practitioners. We would also like to thank Pavel Levin and Themis Mavridis for their valuable input and assistance in publishing this post.