Moving fast, breaking things, and fixing them as quickly as possible

How we use online controlled experiments at Booking.com to release new features faster and more safely

Written by Iskra and Lukas Vermeer.

At Booking.com, experimentation is an important part of our product development cycle. On a daily basis we implement, deploy to production, execute and analyse hundreds of concurrent randomized controlled trials — also known as A/B tests — to quickly validate ideas. These controlled experiments run across all our products, from mobile apps and tools used by accommodation providers to customer service phone lines and internal systems.

Almost every product change is wrapped in a controlled experiment. From entire redesigns and infrastructure changes to the smallest bug fixes, these experiments allow us to develop and iterate on ideas safer and faster by helping us validate that our changes to the product have the expected impact on the user experience.

In this post we will explain how our in-house experimentation platform is not only used for A/B testing, but also for safe and asynchronous feature release. There are essentially three main reasons why we use the experimentation platform as part of our development process.

- It allows us to deploy new code faster and more safely.

- It allows us to turn off individual features quickly when needed.

- It helps us validate that our product changes have the expected impact on the user experience.

Experimentation for asynchronous feature release

Firstly, using experimentation allows us to deploy new code faster. Each new feature is initially wrapped in an experiment. New experiments are disabled by default.

if et.track\_experiment(“exp\_name”):

self.run\_new\_feature()

else:

self.run\_old\_feature()

This means that deploying out new software to production does not directly affect the user experience. Releasing features is by design a separate step from releasing code. This approach allows us to deploy production code frequently with less risk to our business and our users, giving us much more agility in development.

This also means that the person deploying the new code does not need to be aware of all of the awesome new features contained in the release. No detailed documentation explaining what the new code should do is required at this stage, because none of these code changes take effect when code is being deployed. Any observed changes in system behaviour during a deployment can be considered a problem that requires immediate investigation.

The ability to release features asynchronously is possibly the biggest advantage we get from wrapping all of our product changes in experiments. While it is true that a simple feature switch mechanism built for only this purpose would provide the same benefit, adding experimentation on top has further advantages that we will discuss next.

Experimentation as a safety net

Secondly, using experimentation for asynchronous feature release allows us to monitor and stop early individual changes to our products. Since each new feature is wrapped in its own experiment it can be toggled on or off, independently from any other changes. This granular in-flight control allows the specific developer or team responsible for the feature to enable and disable it, regardless of who deployed the new code that contained it.

If there are any unexpected issues after enabling a particular feature, the individual experiment can be stopped in a few seconds, rather than having to revert the entire code base. This allows us to detect and mitigate damage from individual changes very quickly, again giving us more agility in our development and release cycle.

Again, no detailed documentation explaining what the new code should do is required for this step. The developer or team enabling the feature is already keenly aware of what it should — and should not — do, because they designed and developed the feature themselves. The people responsible for releasing a new feature thus already know exactly what things to monitor, and what things to look out for. As a result, we can postpone the time consuming creation of detailed documentation until after the feature has been validated in production.

Our monitoring tools have built-in understanding of our experimentation platform and allow our engineers to group production issues by experiments and their variants. This makes it very easy to pinpoint what change introduced an error and to mitigate it as needed. These tools help our teams balance speed, quality, and risk while introducing new features, but not all risks should be considered equal. We want to move fast and break things, but when the user experience breaks badly we want to unbreak things as fast as we possibly can.

The circuit breaker

Having product feature owners closely monitor their own feature release may not always be sufficient. In rare cases of severe degradation of functionality, we might want to immediately and automatically abort a release to mitigate the impact on the user experience. Although this goes contrary to our core value of fostering ownership and responsibility within product teams, there are situations where protecting users should take precedence.

For example, when a new feature significantly increases the amount of users seeing errors or otherwise unusable pages, we will want to revert that change as quickly as possible regardless of the specifics of the feature being introduced. We simply cannot imagine a scenario in which increasing such user-facing failures would be acceptable.

Broken features of this kind should not make it to production often (new code and features are obviously extensively tested before they are released into production), but we operate in a complex technical environment at global scale and pre-production testing may fail to uncover potential production issues. From a user experience point of view these failures are severe enough to be worthy of our consideration, even if they are infrequent.

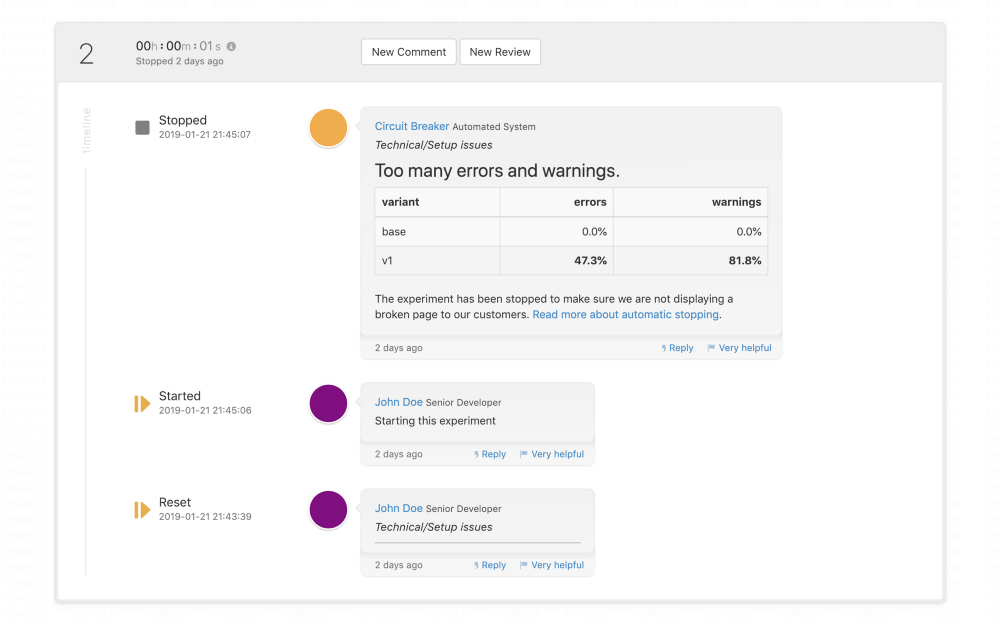

The circuit breaker is an example of an automated system which is part of our safety net. It is active for the first three minutes after any new feature is released, closely monitors for any severe errors or degradations, and automatically aborts a release when significant issues are found. In some cases this happens within a second after starting the release. This means that users who are exposed to such a broken feature will likely only be affected for a single page view, drastically reducing the impact on the user experience.

Circuit Breaker stopped this experiment within a second because it unexpectedly introduced errors for 47% of users that triggered the new code-path.

Our experimentation data pipelines and reporting are quite fast, but they were still designed to always prioritize validity above velocity. However, because the circuit breaker is intended to mitigate immediate and severe user-facing degradation, we are willing to sacrifice some statistical rigour in order to improve response times.

We cut corners in favor of speed in several ways. For example, we test for statistical significance roughly four times per second for a duration of three minutes without any explicit form of correction for multiple comparison. We accept that this will increase our false positive rate and we might accidentally stop an experiment incorrectly. However, the circuit breaker uses a very strict threshold for statistical significance since it is intended to detect only the most severe degradations of the user experience. So far, only one experiment has ever been stopped erroneously, and restarting it was not a problem for the team.

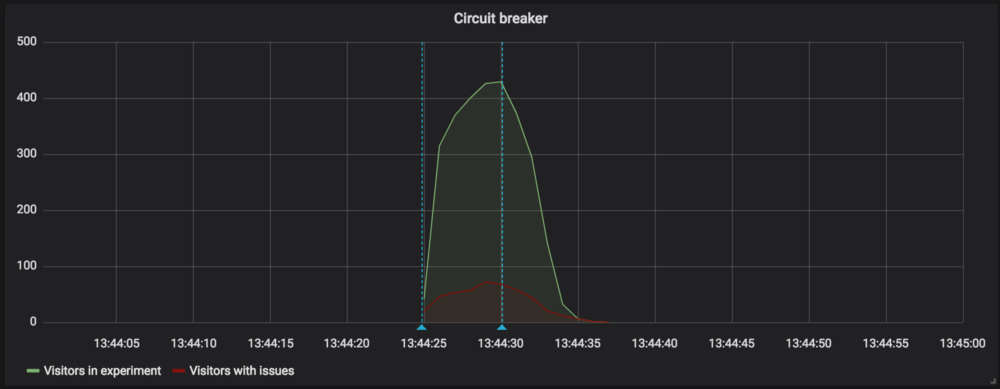

The second corner we cut is that deduplication of visitors is performed in batches of 36 seconds. This approach is imperfect and results in some visitors being double counted, but it allows us to perform the deduplication in-memory on each Kafka consumer, without the need for external storage or state synchronisation over the network. This allows the circuit breaker to respond significantly faster, in some cases even before our generic monitoring tools have completely ingested the necessary data to report results to internal users.

This experiment was stopped before our generic monitoring tool ingested the necessary data to report results to internal users.

These shortcuts also partially explain why the circuit breaker is only active for the first three minutes after a feature is released: running it much longer would result in unacceptably high false positive rates. The tradeoffs made between speed and accuracy, as well as individual ownership and centralized automation, are acceptable when guarding against severe user-facing degradation, but when such critical issues do not become apparent in those crucial first few moments, we once again put ownership and responsibility for monitoring every feature release within our product teams.

Experimentation as a way to validate ideas

Lastly, experiments allow us to measure, in a controlled manner, what impact our changes have on user behaviour. Every change we make is created with a clear objective in mind: a single hypothesis on how to improve the user experience. Measuring the real impact of our changes allows us to validate that we have achieved the desired outcome.

There are always (too) many product improvement ideas that we could work on. Experiments help us learn which changes have impact on the user experience, so that we can focus our efforts on those things that matter most to our users.

Instead of making complex plans that are based on a lot of assumptions, you can make constant adjustments with a steering wheel called the Build-Measure-Learn feedback loop.

— Eric Ries, The Lean Startup

The quicker we manage to validate new ideas, the less time is wasted on things that don’t work, and the more time is left to work on things that make a difference. In this way, experiments also help us decide what we should ask, test and build next.

Conclusion

Our in-house experimentation platform is used for safe and asynchronous feature release. Experiments allow us to deploy new code faster and more safely, to turn off individual features quickly — and in some cases even automatically — when needed, and help us validate that our product changes have the expected impact on the user experience. This emphasis on iterating quickly and learning from real user behavior is why experiments form such an important part of our product development cycle. Moving fast and breaking things safely helps us understand what changes have a measurable impact on the user experience, while at the same time protecting those same users against our inevitable mistakes.

Acknowledgements

This post was loosely based on a paper presented at the 2017 Conference on Digital Experimentation CODE@MIT as well as some of our internal training materials. The ideas put forward were greatly influenced by our work on the in-house experimentation platform at Booking.com, as well as conversations with colleagues and other online experimentation practitioners. We would also like to thank Steven Baguley for his valuable input and assistance in publishing this post.